展覽介紹

法國哲學家保羅•里克爾的話「象徵引發思想」,似乎很能透徹地道出當代藝術所扮演的角色—無關乎它說了什麼,而在於指出了什麼可能。當代的視覺藝術無關乎終點而是旅程,扮演的不僅是已完成的文本角色,它同時也貼合著人性的軌跡、社會的思潮和時代的脈動,企圖引發更多未完成的思想的發聲。 透過五件複合媒材裝置作品,創作者企圖邀請觀者一同參與「光可以是什麼」的無盡想像,而無意提供特定的詮釋觀點。光可以是詩中令人反覆不已的一節;光可以是與自己的久別重逢;光可以是迷霧中的洞察之眼;光可以是純真與經驗的結合;光可以是長長地嘆出:「 I am a human being again! 」

“The symbol gives rise to thought”, a well known saying of the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, seems to thoroughly explain the role of contemporary art. Art is not just about what it says, but also about what possibilities it shows. Art is not a destination – a finished piece of artwork – but a journey, an interpretive process that creates a dialectic between the work, the artist and the audience. Art echoes the life rhythm of its creator and the world he/she lives in. It also reveals traces of humanity, and the ideological trends and turbulences of society by providing avenues for airing unfinished thoughts. Through five installations, the artist intends to invite the viewer to imagine what light could be, instead of providing fixed interpretations or points of view. Light could be a stanza of a poem that makes one ponder long and deeply; light could be a reunion with self; light could be gaining insights in the mist; light could be a happy marriage of innocence and experience; light could be sighing: “I am a human being again!”

創作論述

最近一次被光深深吸引的經驗發生在德國的科隆與柏林,是2008年在德國萊茵河上德意志橋橋墩內進行「在光影間囈語」( Figure 1 )的展演期間。有一晚,我行經萊茵河旁的科隆大教堂(Koln Dom),突然想看看沒有陽光時的教堂內部。夜晚的遊客稀疏,教堂裡空盪而安靜。教堂左右內側點滿了燭火,十分的安祥溫暖,跟白天穿過彩繪玻璃,明亮的上帝之光截然不同。我在木條椅子上靜坐許久,之後起身點燃燭火離。還有一個同樣位於科隆市的Kolumba博物館,它的光也令我永生難忘。建築師在毀壞的地基與殘存的建築體上增建,新舊建築天衣無縫地融為一體,渾然天成,深深感受建築、新結構與斷垣殘壁的合而為一。當自然光從外牆上無數的小方格溢入,照出一室的光影明亮,頓時覺得自己裡裡外外也通透清澈了起來。

I was totally drawn by light when I was in Koln and Berlin in 2008. One night when I was passing the square of Koln Dom, I decided to visit the Dom because I was wondering what it would look like when there was no sunlight shining through the stained glass windows. The interior was quite and only a few visitors were there. The candle flames filled the place with warmth and peace. The warm light emitting from the candles were so different from God’s light through the stained glass windows. I sat on the wooden bench and allowed myself to be showered in candle light. The Kolumba Museum in Kolon also impressed me with the amazing phenomenon of its light. It was built around surviving medieval ruins that were integrated into the new structure to become a perfect whole. The architecture, the ruins and the new structure of the museum are united as one, without seam. I felt as clear as a crystal when touched by the light coming through the countless openings in the wall.

後來在紀念猶太人被納粹屠殺的「柏林猶太博物館」(The Jewish Museum Berlin)也經歷了很特殊的光的經驗,那是在進入漆黑密閉的「浩劫之塔」(Holocaust Tower )中,看到一道光從陡斜的屋頂縫隙直直落下,猶如漆黑宇宙中的一條裂縫,是孤寂的絕望也是一線生機。還有一個意外,就是在水泥牆上發現直徑約3至4公分,如數位相機鏡頭般大小的洞,當眼睛緊緊貼在洞口上時,可以感受到外面的光( Figure 2 ),但因視角有限而看不到足以瞭解外在世界的景物。這些光的現象充滿了富饒的隱喻,從約伯的苦難、納粹的毒氣室,到廣島毒蕈般的原子彈爆炸,它到底要告訴我們什麼?是天地不仁?還是神是暴怒和愛復仇的?除了以上這些經由視覺經驗所引發的光之感知外,我還想從閱讀及其他方面來談「光」。

I also had a very special experience when I was at the Jewish Museum, Berlin. In the complex stands the dark, isolated and enclosed Holocaust Tower. A light beam pierced through the roof corner like an opening from a mysterious universe – a glimpse of despair, as well as a gleam of hope for survival. Discovering holes in the wall 3 to 4 cm in diameter – almost the same size as a digital camera lens – was another surprise. However, I was unable to see what was happening on the other side of the wall when I put one eye against the hole due to the limited angel of my eyesight. All of the phenomena of light that I have mentioned here are living metaphors. From Job’s sufferings, Nazi gas chambers, to the atomic explosion at Hiroshima, what messages have we got? The Tao doesn’t take sides? God is wrathful and revengeful? Or is there something else? Besides the above perceptions inspired by visual experiences, I would like to talk more about light from my reading and other perspectives.

讀大江健三郎所寫的1994年諾貝爾文學獎得獎感言「Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself」時,得知他有一位兒子名Hikari,是「光」的意思。之後再看了他的「A Personal Matter」和「A Healing Family」才知道到「光」這個名字更深一層的涵意。原來孩子是一個腦有所缺陷的新生兒,大江健三郎內心曾盼望醫生不要救他。而在這天人交戰的一念之間,孩子被給予一個機會存活了下來,並被命名為「光」。但光的深刻意義卻是隨著Hikari與親人之間的互動才逐漸顯露的,Hikari的生命如一點燭光,雖微小,但因在漆黑中而顯得特別明亮,不僅讓他自己與身邊的生命燃燒、發光發熱,也讓我們在幽幽隧道中看到了出口處的光亮。這是我與「光」在文學上的第一次相遇。

From reading Kenzaburo Oe’s “Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself”, I came to know that his first child was born mentally handicapped. When he first saw his baby lying in the hospital crib, he hoped the baby could not survive. After much struggle, he accepted the infant as a member of his family and named him Hikari, meaning “light” in Japanese. The dim light lightens the darkness while Hikari and Oe’s life story unfolds. It invites us to see light at the end of the tunnel. This was my first encounter with “light” in literature.

初次看蘇俄導演塔可夫斯基的電影「鄉愁」,無法理解片中的作家Gorchakov為何要執意手持飄忽不定的燭火,費力地保護它渡過St. Catherine pool。在抵達池子的另一端時,Gorchakov同時心臟病發而亡,而早先將蠟燭託付給他的Domenico也在另一個城市引火自焚,以犧牲的方式來拯救自己、家人和全世界。Domenico自焚前曾發表連續三天的演說,其中一句話是:「…Fuel the wish…」,我聽了才豁然明白「光」的另一層意義。當貝多芬第九交響曲的快樂頌突然響起,而渾身是火的Domenico在廣場上翻滾時,我完全無法言語;另一個類似,但平和許多的經驗是聆聽Philip Glass的歌劇 Satyagraha時,感受到甘地的非暴力抵抗及不合作主義為人類所點燃的珍貴希望。這是我與「光」在電影與音樂上的再度相逢。

At the beginning, I did not understand why Gorchakov, the Russian writer in Tarkovsky’s film “Nostalgia,” moving at a snail’s pace and protecting the flame of a candle-end from gusts of wind, intended to approach the portico of Saint Catherine’s pool. He died from a heart attack just as he painstakingly reached it. In another city, Domeico, the man who entrusted the candle to Gorchakov, set himself on fire to save himself, his family and the whole world. When I caught the words “…fuel the wish…” in his non-stop three-day speech delivered to the public in the square before his sacrifice, the meaning of “light” came to me again. I was awed by seeing Domeico rolling on the square in flames with Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” bursting out in the background. This was my second encounter with light in film and music. Another similar experience, but not so dramatic, was listening to Philip Glass’s opera piece “Satyagraha”. It reminds me of Gandhi who lit up another precious candle for humankind.

在繪畫上,若要談光,不論就哪一個層面而言,很多人會想到林布蘭,但我想談的是墨西哥新表現派的畫家 Julio Galán(1958-2006)的一幅作品 Portrait of Luisa (1990)。畫中有著棕色短髮的Luisa坐在椅子上,側著頭,貼靠在覆蓋著直條紋蘋果綠桌巾的方桌上小睡,桌上有一只咖啡色大花瓶,裡面插著稠密的暗紅色花朵,花瓶守護著Luisa熟睡的白皙臉龐,淡淡紫羅蘭色的背景、懸浮的方框與圓環輕繞著柔軟的帶子與半透明的絲巾,告訴我們她正在睡夢中。一個黑亮的小球體懸浮在有著隱隱光環的正圓中,虛無透明,直直地看著觀者,猶如一隻如夢的眼睛,透出知曉的光,就像面紗掩不住光暈,輕輕地、迂迴間接地流溢過來,把兩個世界連接了起來。這是我與「光」在繪畫上的低聲私語。

In painting, Rembrandt’s works come to most people’s minds when speaking of light, no matter what the aspect. However, the painting “Portrait of Luisa” by Julio Galán (1958-2006), a neo-expressionist painter, is what I choose to talk about here. In the painting, the female figure Luisa is taking a nap on a chair. She rests her cheek on a table covered with a striped green table cloth. A brown vase with red flowers is centered on the table, right by Luisa’s pearl-like cheek. The vase, as a guardian angel, protects the sleeping Luisa from disturbance. The suspended frame-like rectangle and black ring with floating silk strips winding through it, together with the subtle violet background, tells us that Luisa is in a dream. A floating black ball with an aureola, a dream-like eye, reveals the light of knowing. Light permeates through the veil, and thus the two worlds are connected. This is my whisper with light in painting.

當我讀到法國哲學家保羅•里克爾對伊底帕斯神話的詮釋時,看到瞎眼的先知Tiresias能洞見真理,而雙目能見的Oedipus卻被自己的憤怒與無知蒙蔽。盲人比明眼人看得更透澈,這時我體會了「內在之光」的意義。這是我與「光」在哲學上的目光相交。

Paul Ricoeur said, the core of the tragedy of Oedipus is the problem of light. “The seer is blind with respect to the eyes of his body, but he sees the truth in the light of the mind. That is why Oedipus, who sees the light of day but is blind with regard to himself…” (1970). Reading his interpretation, I realized the meaning of “light from within”. This is my eye contact with light in philosophy.

在這個展覽中,我轉化從建築、文學、電影、音樂、繪畫和哲學而來的所思,折射成五件複合媒材裝置作品,企圖表達光可能是什麼,其中的符號是象徵的,意義是多層、流動的,訊息是個人、隱晦的。觀看的人可以選擇以私密或一般認知的角度來想像或經驗這些作品,其詮釋是開放給觀者的。最後以一段冰雪記憶,來為「內在之光」做序幕,是Leonard Cohen作的詞曲,發表於2004年的歌曲 “Dear Heather”。當然它也是一首詩,一段吟唱,一個想望,一個揮之不去、栩栩如生的影像,也是我反覆的祈禱,不論看得見或看不見,聽得見或聽不見。

Inspired by previous encounters of light in architecture, literature, film, music, painting and philosophy, I reflected on them and transformed my thoughts into five installations. My intention is to express what light could possibly be. The visual symbols are metaphoric; the meanings are unfixed and weaved into layers; the message is personal and ambiguous. The viewers are free to choose any unique or general perspective to imagine or experience the installations. The interpretation is open to the audience. In the end, I would like to bring my deeply inscribed memory of Leonard Cohen’s music, lyrics and vocals of “Dear Heather” forward as the prologue of this exhibition. It is a poem, a chant, a wish, a lingering imagery, and a prayer of mine. No matter if it can or cannot be heard; can or cannot be seen.

Dear Heather

Please walk by me again

With a drink in your hand

And your legs all white

From the winter

Dear Heather

Please walk by me again

With a drink in your hand

And your legs all white

From the winter

作品巡禮

01

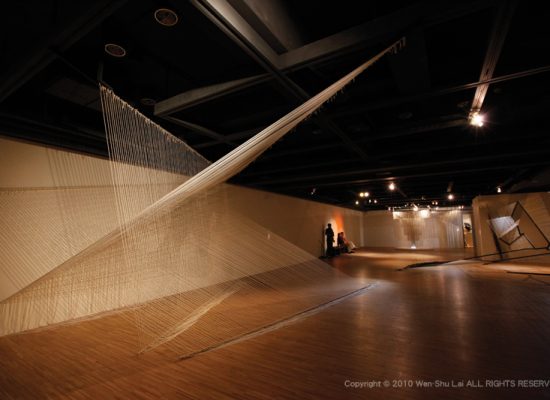

他者與自身-謎般之流

The Other and Self – An Enigmatic Stream

棉線、金屬網格、玻璃、木材、燈管裝置視空間大小而調整尺寸

Cotton rope, metal grids, glass, wood, and LED Installation varies on location. 2010

不論看到的是自己的或別人的,內在的或外在的光,

其實都是同一個,都是與自己的重逢。

Seeing one’s light or the light of others, inner or outer, is in fact a reunion with self.

02

鏡像.盲眼明人 Mirror Image.Blind Seer

墨水、燈管、木框 裝置視空間大小而調整尺寸

Ink, light, and wooden frame 395cm x 260cm x 50cm Installation varies on location. 2010

作品是回應Paul Ricoeur對伊底帕斯神話的詮釋和 St. John of the Cross的詩作,

兩者都是關於內省與察覺。詩句節錄自“On a dark night”一詩,

英文字體則由創作者根據1475年William Caxaon的字體重建而來,

該字體是出自以英文印刷的第一本書籍。

This piece is a response to Ricoeur’s interpretation of the “Oedipus Myth” and St. John of the Cross’s poem “On a dark night”. The type used in the poem is designed by Wen-Shu Lai and is derived from the type used in the first book printed in the English language by William Caxton in 1475.

03

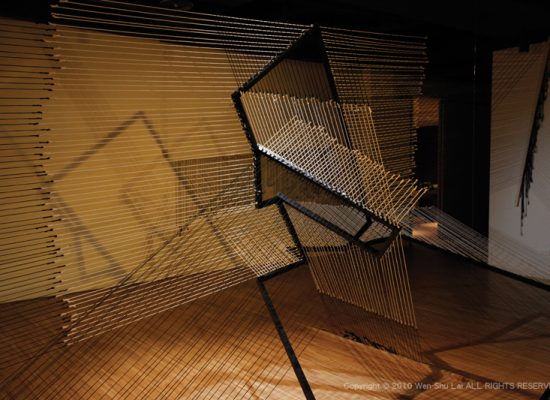

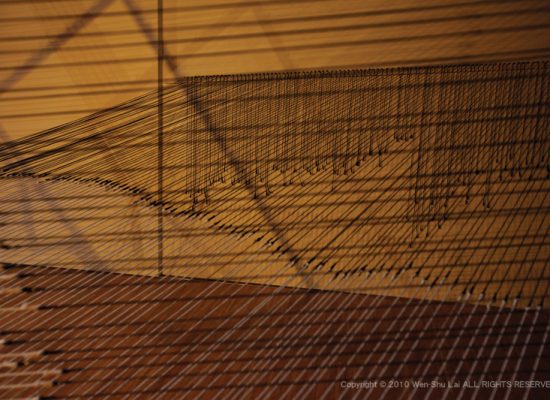

化身.連結 Avatar.Connector

木材、棉繩、尼龍繩 裝置視空間大小而調整尺寸

Wood, cotton and nylon rope 5m x 5m x 5m Installation varies on location. 2010

沒有任何事件或人是全然獨立存在的,看似無關的,

皆以巧妙的方式連結在一起,而結束也正是起點。

The installation looks like a connection of strings in life. So many strings lead to other strings, yet sometimes they lead no where and sometimes they bring you back to the same point – where you started.

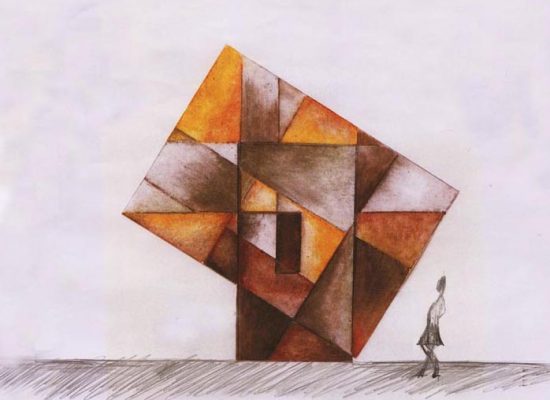

04

睡與醒 Sleeping and Waking

木材、棉繩、黑色紙膠 裝置視空間大小而調整尺寸

Wood, cotton rope, and black tape 5m x 5m x 5m Installation varies on location. 2010

原本是一件思考虛實空間的作品,但也對應著生命的睡夢與清醒,

記起與遺忘,兩者互為對方的夢鄉。

This piece originally studied positive and negative space, virtual and real. Yet, it also reflects the state of life: sleeping and waking, or remembering and disremembering – the one maybe the dream of the other.

展覽單位/執行單位